In the 2022 film, Banshees of Inisherin, Colm Doherty’s motivation may not have been fully appreciated amidst the story’s intensity. Doherty wanted to avoid smalltalk at any cost because he realized he had become old and the end was near, so if he was going to leave any meaningful legacy, he had to focus exclusively on his musicianship.

I wonder if we avoid questions of legacy out of a fear of being forgotten. Will anyone remember? If so, who? And what will they remember? And for how long?

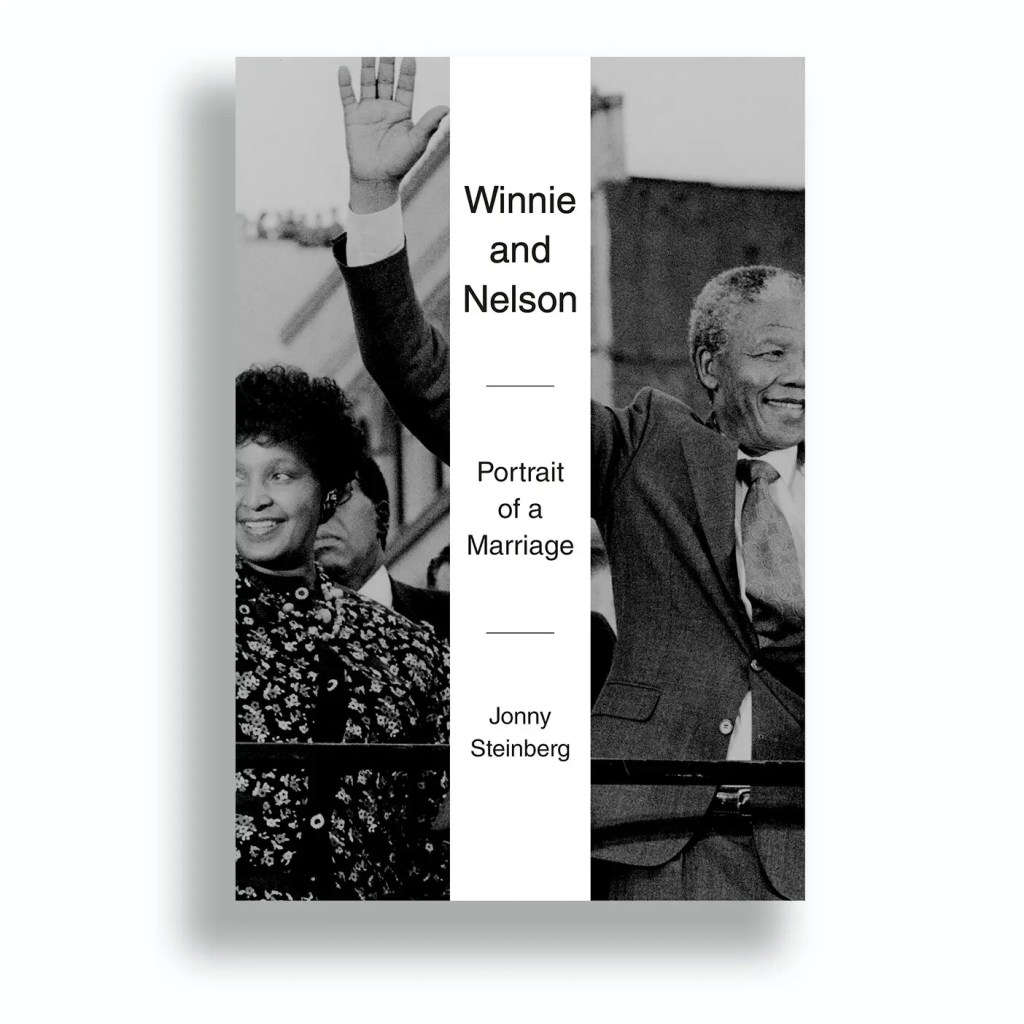

Enter Jonny feckin’ Steinberg, author of Winnie and Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage. I predict Steinberg’s book will be the go-to source for understanding the end of apartheid for hundreds of years. I read it because I followed the anti-apartheid struggle closely in my twenties and I wanted to learn more about two of the central characters. And not knowing much about their marriage, I suspected there would be some salacious details.

Almost immediately though, I got distracted by Steinberg’s brilliance, constantly wondering how he managed telling such a complex and intimate story in the most intelligent way imaginable. Surgical is the word that springs to mind. Steinberg, working mostly from a 15,000 page file illegally held on to by one of the government’s top security officials, repeatedly takes readers inside the Mandela’s relationship, into Nelson’s Robben Island prison cell, inside the African National Congress’s machinations, and onto the streets of the Soweto uprising.

The descriptive writing is good, but what’s most exceptional about the book is Steinberg’s masterful interpretation of documents and events. It’s an ingenious example of historiography or how history should be written. Sometimes Steinberg opts for humility and uses tentative language such as “Although we can never know for certain, . . .” At others, he fearlessly calls into question both central characters’ veracity, especially Nelson’s. Most of the time though, he’s helpfully splitting the difference, thoughtfully offering a particular interpretation based upon the precise historical context and the preponderance of evidence. Very early on, Steinberg’s brilliant interpreting and reasoned judgement caused me to conclude that he was the most credible of narrators.

Steinberg’s acknowledgements reveal that he had eight editors across three publishing houses. And he’s generous in crediting his research assistant, several archivists, and numerous readers of his drafts. Writing may be a solitary endeavor, but publishing a seminal work of this nature, clearly is not.

In terms of the story itself, first and foremost, one can’t help but be overwhelmed by the scale of the government’s persistent human rights abuses and violence, but also the black-on-black violence it engendered.

Another lasting lesson is that the media places individuals on pedestals, whether Barack Obama, Angela Merkel, or Volodymyr Zelenskyy by limiting coverage of their failings, both personal and political. For if we get too close, we will always find, just like with Nelson and Winnie, the famous aren’t just fallible, they’re extremely flawed.

There are many other take-aways. While an imperfect analogy, I came to think of Nelson as a Martin Luther King like thinker and activist and Winnie as a female Malcom X. This tension begs important questions including how does social change happen, nonviolently or violently, slowly or quickly? And if changing a violent regime requires its own violence, how do the survivors turn off that spigot?