The conversation turned to real estate on a recent Saturday run when I shared my opinion that many sellers in our community were slow to grasp the correction as evidenced by their overpriced houses languishing on the market for six months to a few years.

You would have thought I suggested we extend our 10 miler another 16.2 just for the fun of it. The right wing nutters immediately jumped on me for assuming I knew more about free markets and home values than the actual homeowners themselves. And more importantly, who did I think I was, homeowners have the right to price their houses however they want.

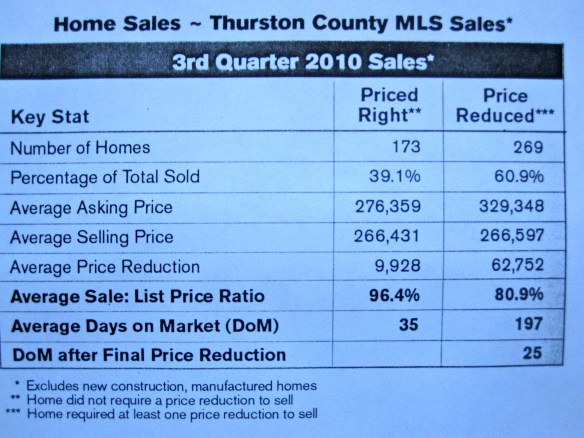

Of course they do just like they have the right to be irrational and waste money more generally. Check out this chart:

In the end, the average “priced right” and “priced reduced” home sell for the same price, but the “price reduced” home is on the market an extra 162 days. If “price reduced” homeowner has $100k in equity, and that equity was invested for 162 days @ 5%, they passed on earning $2,219. That’s the cost of exercising your constitutional right to overprice your home.

Around here at least, it appears that the larger and more expensive the home the greater the tendency to overprice it. That’s counterintuitive if one assumes, on average, the most well-to-do homeowners are the most business savvy, but I digress. We can also assume a much smaller pool of prospective buyers (I know it only takes one) and therefore the “average days on market” I suspect is far greater than 197, but for consistency sake we’ll stick with that.

Let’s consider a waterfront home that is four times the average at $1,317,392. Ultimately, after 197 days, overpriced sellers have to reduce their price $251,008 ($62,752 x 4). Let’s compensate for the too short “average days on market” by assuming that our waterfront sellers own their home outright. If “expensive price reduced” homeowner has $1,066,384 (the final sale price) in equity and had invested that for the too short 162 days @ 5%, they passed on earning $23,665.

To which the nutters might say, “That’s waterfront sellers right.” Which again, of course is right, just irrational.

Since I’m on math fire, and the nutters are down for the count again, one related thought. One oft repeated housing axiom is that housing corrections don’t matter if you’re buying and selling into the same down market. That’s only true in one of three possible scenarios—buying and selling similar priced homes. It doesn’t hold for buying a more or less expensive home than sold.

For example, consider the case of buying a more expensive home. Imagine you could sell your existing home for $300k or $100k less than its peak 2007 valuation. You buy a home for $1m or $250k less than its peak 2007 valuation. Had you made that move in 2007, it would have cost $1,250,000-$400,000 or $850,000. Today, the equation is $1m-$300,000 or $700,000 for a savings of $150k.

The opposite is also true. As a result of the correction, it’s more expensive to move down. Imagine you could sell your existing home for $600k or $200k less than its peak 2007 valuation. You buy a home for $300k or $100k less than its peak 2007 valuation. Had you made the move in 2007, you would have pocketed $400k, $800k sale price-$400k purchase price. Making that move today you would only pocket $300k, $600k sale price-$300k purchase price.

So assuming one has the resources, it makes more sense to move up in down markets and down in up markets.

School’s out nutters. Do they give out Economics Nobels for this stuff?