- MacKenzie Scott Gives $436 Million to Habitat for Humanity.

- World No. 1 Ash Barty, 25, Announces Retirement from Tennis.

- Afghanistan’s last finance minister, now a D.C. Uber driver, ponders what went wrong. Semi-related, no prime minister of Pakistan — a country that has swung between democracy and dictatorship — has ever completed a full term in office (The Financial Times).

Monthly Archives: March 2022

Tuesday Required Reading

- Girls flag rugby. Beautiful lead picture. Of course the red-head is kicking ass.

- UCLA reverses course and will pay the adjunct professor after all. HR clown show.

- How much do the best pro cyclists make? “. . . pocket-money compared to some of the world’s wealthiest sports.”

- Right on. My Covid guy gets the top job. Everyone has a Covid person or team that affirms their preconceived notions about all things ‘rona. Ashish Jha is mine.

Stop And Go

People who evaluate the viability of a commute to work often error in only considering the distance. They’ll decide 10 miles is doable, 15 or 20 is not. But anybody who has commuted much at all knows it’s not that simple because an uninterrupted 15 or 20 mile drive is way better than a 10 mile one in stop-and-go traffic. Because the constant changing of speed and monitoring of space is mentally exhausting.

Which brings me to college basketball’s March Madness, one of our country’s greatest sporting events.

I watch a fair amount of television sports, but because I’m impatient, about two-thirds of that viewing is shortly after the event is over so that I can fast forward through the endless commercial breaks. Not just that, sometimes I watch basketball games and golf tournaments in “2x” speed, which is a fair bit faster than real time. I also fast forward through field goals and free throws, deducing the outcome of them from the score change. Given my advanced remote control skills, I can watch a 40 minute college basketball game in about. . . 40 minutes.

Which brings me to Saturday’s West Regional in Portland, Oregon where I watched UCLA turn up the defensive intensity against St. Mary’s in person and advance to the Sweet Sixteen Friday in Philadelphia.* It was WEIRD watching the game in very real time because of the incessant breaks in the action.

Like driving in stop-and-go traffic, the game is played in twelvish two to four minute segments. That’s because each team gets a certain number of timeouts and then there are pre-planned “television timeouts”. To add insult to injury, now soul crushing video replays of especially close officiating calls make the spectating an even greater test of patience.

How is any team supposed to sustain any momentum? And how are fans expected to stay tuned in through the millions of mind numbing commercials?

It’s enough to make someone want to watch soccer.

*I watched some other team beat some other team too.

Let The Madness Begin

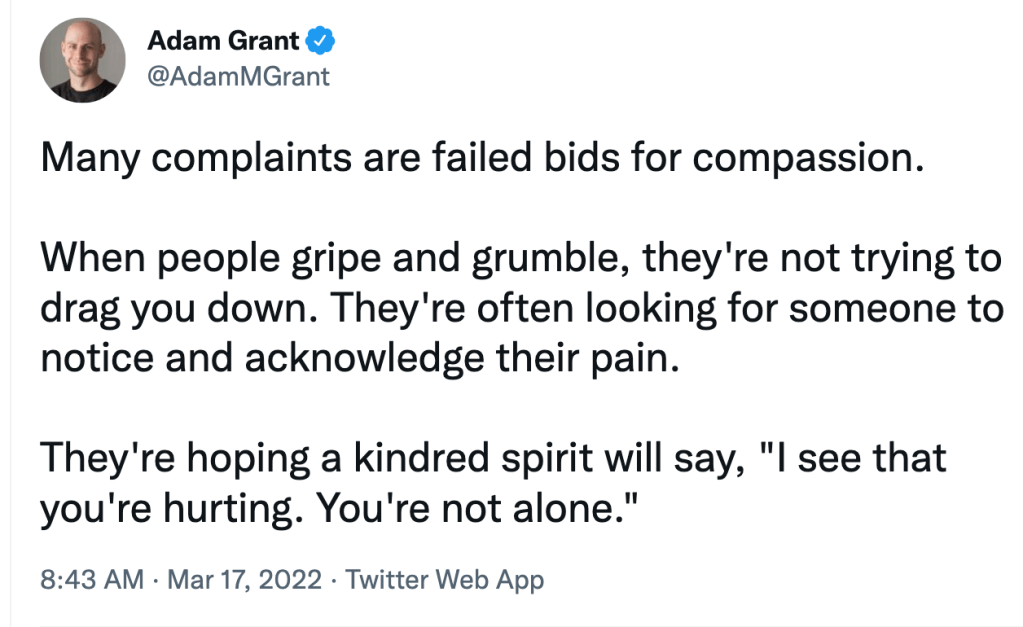

Why We Complain

Image

Symbolism Over Substance?

I am fortunate to live in Olympia, Washington in the upper lefthand corner of the (dis)United States. This morning I did one of my fave runs. To Priest Point Park, a loop of the heavily wooded east-side trail, and back, 7.5 miles for those keeping score at home. Now I’m sitting at my desk looking alternatively at my computer monitor and Budd Inlet, the southernmost part of the Puget Sound, a series of saltwater inlets that are, in essence, a bucolic part of the Pacific Ocean.

But did I really run to Priest Point Park and am I really sitting above Budd Inlet? Indigenous groups are succeeding in renaming places based upon their history. Now, Budd Inlet is more appropriately called the Salish Sea and the Olympia City Council is in the process of renaming Priest Point Park, Squaxin Park, after the Squaxin island tribe, who lived here first.

I am down with the updating, but I wonder about a potentially subtle, unconscious even, unintended consequence. What if we think land acknowledgement in the form of updated place names is sufficient and stop short of more substantive changes that would both honor Indigenous people’s history and improve their life prospects?

Of course it doesn’t have to be either/or, it can and should be both/and, but we seem prone to superficial, fleeting acts that are often “virtue signaling“. We change our blog header to Ukraine’s flag, we put “Black Lives Matter” stickers on our cars, and otherwise advertise our politics in myriad ways, but we don’t always persevere. With others. Over time. To create meaningful change.

What is the state of the Black Lives Matter movement? How much attention will the media and public be paying to authoritarianism in Eastern Europe a year or five from now?

Admittedly, that’s a cynical perspective, but I prefer skeptical. I’m skeptical that substituting the Salish Sea for Budd Inlet and Squaxin Park for Priest Point Park will do anything to protect salmon, extend educational opportunities for Indigenous young people, educate people about our Indigenous roots, or improve Indigenous people’s lives in the Pacific Northwest more generally.

In fact, I wonder if it may, in an unfortunate paradoxical way confound those things. I hope not.

Spreading Kindness

Inspired by Ann Braden’s “Flight of the Puffin” fourth and fifth graders are making and sharing kindness cards with people in their school community.

Fifth grader Hazel Uvenes reflects:

“The person who gets the card knows that they are kind and different and amazing in their own way. I think it’s really great because sometimes the littlest things can bring somebody out of a bad day.”

She added:

“I think maybe it could uplift their spirit a lot, and they feel like they can have fun, they believe in themselves, they can be kind to others. . . “

Soon the students will share their kindness cards with local organizations in order to brighten even more people’s days.

Schools Remain Sites Of Joy

Hey school principals, pay even closer attention to positive emotions and experiences.

Applies to leaders of all sorts. Scratch that, people of all sorts.

From Education Week, “Rx for Principals: Take in the Joy”.

“. . . almost 45 percent of principals said they had considered leaving their jobs or sped up their plans to exit the principalship because of COVID-related working conditions.

Yes, working conditions for principals have been tough. But that’s only part of the story. Even in the current circumstances, schools remain sites of joy. Principals regularly experience this joy, and it could make a big difference in how they perceive their working conditions.”

Let’s start asking principals. . . and others. . . about their most positive experiences.

“If you ask principals about their positive experiences, you will hear a steady stream of stories and see their faces light up with smiles. For example, an elementary school principal in an urban district described being moved to tears seeing an English-learner student, after a difficult year of transition, reading in two languages. Another principal talked about how meaningful she found coaching a novice teacher who was struggling but also improving by the day. Such experiences too often go unnoticed and unshared.”

What have been your most positive recent experiences?

The ‘Thin Veneer’

The United States Free Fall Starts Here

With a decline in public support for public education and a concomitant decline in quality.

George Packer in The Atlantic argues that we’ve turned schools into battlefields, and our kids are the casualties.

“It isn’t clear how the American public-school system will survive the COVID years. Teachers, whose relative pay and status have been in decline for decades, are fleeing the field. In 2021, buckling under the stresses of the pandemic, nearly 1 million people quit jobs in public education, a 40 percent increase over the previous year. The shortage is so dire that New Mexico has resorted to encouraging members of the National Guard to volunteer as substitute teachers.

Students are leaving as well. Since 2020, nearly 1.5 million children have been removed from public schools to attend private or charter schools or be homeschooled. Families are deserting the public system out of frustration with unending closures and quarantines, stubborn teachers’ unions, inadequate resources, and the low standards exposed by remote learning. It’s not just rich families, either, David Steiner, the executive director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, told me. ‘COVID has encouraged poor parents to question the quality of public education. We are seeing diminished numbers of children in our public schools, particularly our urban public schools.'”

Packer states what’s increasingly obvious:

“The high-profile failings of public schools during the pandemic have become a political problem for Democrats, because of their association with unions, prolonged closures, and the pedagogy of social justice, which can become a form of indoctrination. The party that stands for strong government services in the name of egalitarian principles supported the closing of schools far longer than either the science or the welfare of children justified, and it has been woefully slow to acknowledge how much this damaged the life chances of some of America’s most disadvantaged students. The San Francisco school board became the caricature of this folly last year when it spent months debating name changes to Roosevelt Middle School, Abraham Lincoln High School, and other schools with supposedly offensive names, while their classrooms remained closed to the city’s children. Republicans have only just begun to exploit the fallout.”

And then concedes he’s “not interested in joining or refereeing this partisan scrum.” Poignantly adding:

“Public education is too important to be left to politicians and ideologues. Public schools still serve about 90 percent of children across red and blue America. Since the common-school movement in the early 19th century, the public school has had an exalted purpose in this country. It’s our core civic institution—not just because, ideally, it brings children of all backgrounds together in a classroom, but because it prepares them for the demands and privileges of democratic citizenship. Or at least, it needs to.

What is school for? This is the kind of foundational question that arises when a crisis shakes the public’s faith in an essential institution. “The original thinkers about public education were concerned almost to a point of paranoia about creating self-governing citizens,” Robert Pondiscio, a former fifth-grade teacher in the South Bronx and a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, told me. ‘Horace Mann went to his grave having never once uttered the phrase college- and career-ready. We’ve become more accustomed to thinking about the private ends of education. We’ve completely lost the habit of thinking about education as citizen-making.'”

Packer and Pondiscio nail it.