See the second picture with the refrigerator on the back.

Tag Archives: green energy

Rooting for the Millennials

Car makers are worried.

Today’s teens and twenty-somethings don’t seem all that interested in car ownership. Or driving more generally. Less than half of potential drivers age 19 or younger had a license in 2008, down from nearly two-thirds in 1998. The fraction of 20-to-24-year-olds with a license has also dropped. And adults between the ages of 21 and 34 buy just 27 percent of all new vehicles sold in America, a far cry from the peak of 38 percent in 1985.

Jordan Weissmann in the Atlantic writes, “The billion-dollar question for automakers is whether this shift is truly permanent, the result of a baked-in attitude shift among Millennials that will last well into adulthood, or the product of an economy that’s been particularly brutal on the young.”

I’m guessing both and.

Wiessmann asks why purchase a new car given the five figure cost, insurance, repairs, and $4/gallon gas, especially if there are reasonable, nearby alternatives like a Zip Car membership, bicycle sharing program, or subway?

Also Millennials are more likely than past generations to live in cities, about 32 percent, somewhat higher than the proportion of Generation X’ers or Baby Boomers who did when they were the same age. But as the Wall Street Journal reports, surveys have found that 88 percent want to live in cities. When they’re forced to settle down in a suburb, they prefer communities which feature plenty of walking distance restaurants, retail, and public transportation.

“If the Millennials truly become the peripatetic generation,” Weissmann warns (emphasis added), “walking to the office, the bus stop, or the corner store, it could mean a longterm dent in car sales. It’s doubly problematic (emphasis added) if they choose to raise children in the city. Growing up in the ‘burbs was part of the reason driving was so central to Baby Boomers’ lives. Car keys meant freedom. To city dwellers, they mean struggling to find an empty parking spot.”

Josh Allan Dykstra in Fast Company asks, “What if it’s not an ‘age thing’ at all? What’s really causing this strange new behavior (or rather, lack of behavior)? He likes the thinking of a USA Today writer who blames (emphasis added) the change on the cloud, the heavenly home our entertainment goes to when current media models die. Dykstra writes, “As all forms of media make their journey into a digital, de-corporeal space, research shows that people are beginning to actually prefer this disconnected reality to owning a physical product.”

“Humanity,” he contends, “is experiencing an evolution in consciousness. We are starting to think differently about what it means to ‘own’ something. This is why a similar ambivalence towards ownership is emerging in all sorts of areas, from car-buying to music listening to entertainment consumption. Though technology facilitates this evolution and new generations champion it, the big push behind it all is that our thinking is changing.”

I like Wiessmann’s and Dykstra’s analyses and insights, but not their conclusions. They’re singleminded focus is on twentysomethings’ impact on economic growth as if everything valuable in life hinges on sales receipts. Ultimately, they’re coaching car makers on how to entice Millennials back into the market.

I’m more interested in cheering them on. For resolving to live differently than their parents, meaning within their means. For caring about the quality of the environment for future generations. For contributing to our country’s energy independence and making it less likely we’ll fight foreign wars. And for challenging the status quo of conspicuous consumption.

At the risk of overgeneralizing, an inspiring generation.

Erring on the Side of Student Smarts

When asked what was most memorable about high school, my first year university students talk about play performances; athletic competitions; service club activites; and jazz band, choir, or orchestra concerts and trips. Their coursework is forgettable, too often even mind numbing. Why?

In part, because they’re rarely asked difficult open-ended questions upon which reasonable people in the “real world” disagree. Too few adults respect students’ intelligence. Also, we lazily and artificially carve up the subject matter into smaller pieces called math, science, language arts, social studies, foreign language, and art—and thereby fail to frame lessons, units, and courses around especially challenging questions.

I’m in the earliest stages of a new project—curriculum writing for a team of explorers who hope to engage large numbers of students in different parts of the world through their expedition to the South Pole in eleven months.

My plan is to err on the side of student smarts and engage middle and high school students through a series of challenging case studies that rest on open-ended questions upon which reasonable people disagree. If successful, the cases will help teachers help students not just learn factual information about fresh water flashpoints around the world, but also to listen, read, and write with greater purpose; think conceptually; and develop perspective taking, teamwork, and conflict resolution skills.

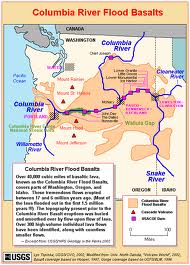

I’m just getting started. Last week I finished an excellent book about the Columbia River that I highly recommend, A River Lost: The Life and Death of the Columbia (second edition). The author, Blaine Harden, is an excellent story teller. It’s required reading if you live in the Pacific Northwest. The primary question raised by Harden is what’s the best way to operate the world’s largest hydroelectric system? Harden’s story centers on a confounding mix of economic interests, biological imperatives, and environmental values.

Most of the players in the drama defend the numerous dams that have turned the Columbia into a “machine river”—electric utility providers; irrigators and farmers; tow barge operators; boaters, windsurfers, and waterskiers; Google, Amazon, and Microsoft with their newish server farms; and elected officials and lobbyists who look out for the interests of utilities, irrigators, the internet goliaths, and other river users. The “other side” consists of Indians whose economic, nutritional, and spiritual lives were built around salmon, and fish biologists and Western Washington environmentalists who advocate for environmental restitution.

Students will research, debate, and decide among three possible outcomes:

- In the interest of maximum economic growth and inexpensive electricity, maintain the status quo of the “machine river”.

- In the interest of compromise and moderate economic growth, allow more water to flow over the dams thereby slightly reducing the total electricity available while simultaneously increasing the number of salmon in the river.

- In the interest of environmental restitution, the return of historic salmon runs, and revitalized Indian life, remove the dams and allow the river to return to it’s natural state.

Teachers will assess the relative thoroughness and thoughtfulness of each team’s proposed outcome. More specifically, they’ll be deciding which is most persuasive and why. Interestingly, this “Machine River” case study has real urgency because a federal court in Portland has given the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration until January 1, 2014 to submit a plan on how best to proceed. Many people whose livelihood’s will be dramatically effected by the outcome are anxiously awaiting the Court’s plan.

Even more challenging than evaluating the costs and benefits of the different possible outcomes, is extrapolating “lessons learned” from the Columbia to other river systems in other parts of the world. For example, Vietnam is upset that Laos is planning to dam the Mekong River. Here’s a question upon which I’ll base an “extension” or “enrichment” activity: Based on Columbia River “lessons learned”, how would you advise Laotians and Vietnamese officials to proceed on the Mekong River? Why?

Even more challenging than applying Columbia lessons to the Mekong is developing a set of principles for 21st Century development more generally. How can local communities, sovereign nations, and international groups maintain healthy economies without compromising natural environments? Or more simply, how do we build vibrant, sustainable communities?

I have more questions than answers. Which is the single best formula for revitalizing schooling.